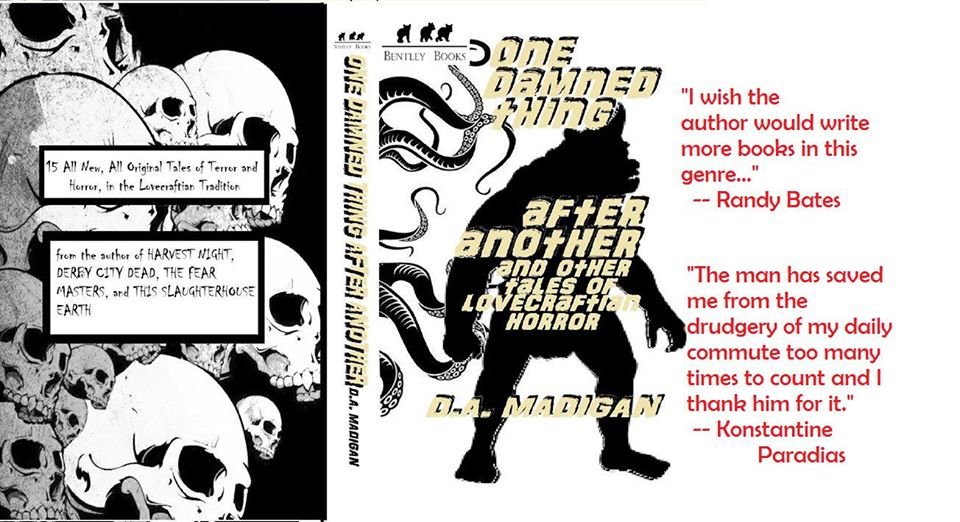

16 Original Stories In The H.P. Lovecraft Tradition -- And They Saved The Creepiest, Scariest One For Last

LIFE'S

A BITCH – AND THEN YOU DIE

I

didn't remember much of the accident... the sudden smashing metal and

glass sound of the impact, somewhere behind me, and I'd have thought

it was someone else's car except that I was suddenly slammed

backwards into my seat with a rattling thump while my old Chevy was

shoved forward and outward, towards the shoulder of the road, and I

saw the rusty metal guardrail filling the right side of the

windshield and the passenger side window and then –

--

a long hallway. Dark, but there was an open door at the end and a

bright light shining out of it, and me hurrying up the hall, jogging,

running, sprinting, except I wasn't breathing hard and can't remember

now the feel of my feet hitting the floor, my arms pumping, sweat on

my forehead –

But

I reached the doorway and stepped through it, and... here I was...

all

stories copyright 2019 D.A. Madigan

A

Bentley Book

For

John Auber Armstrong

“But

the war's still going on, dear

and

there's no end I can see

And

I can see forever...”

one

damned

thing

after

another

&

OTHER TALES OF LOVECRAFTIAN HORROR

D.A.

MADIGAN

Introduction

– Eldritch Musings 1

The

Webbing Between The Worlds 11

Good

Cop, Bad Cop 85

Filters 111

The

Cubicle Beyond Time And Space 125

The

Night They Drove Cro Magnon Down 130

The

Darkness Between The Stars 143

The

Final Incantation 175

The

White House Cylinders 216

Fish

Out of Water 239

The

Fifth Season 286

One

Damned Thing After Another 318

Lovely,

Dark and Deep 333

Which

Can Eternal Lie 342

Charlie

In The Box 354

Pop

Up 384

ELDRITCH MUSINGS

I

admit it – I came to Lovecraft relatively late in life.

I

first read “The Color Out of Space” when I was a 19 year old

college student at Syracuse University. At that time, all

Lovecraft's work had been reissued in a series of paperbacks with

stunning Michael Whelan covers that you couldn't help but come across

in any chain bookstore's SF/FANTASY section.

Strangely,

given the stuff's prevalence – I mean, some publisher must have

thought it would sell, right? -- I didn't know many people who

actually read Lovecraft. I mean, all my acquaintances read sci fi

and fantasy, we all had extensive personal libraries, but there

seemed to be a universal distaste for Lovecraft that, looking back on

it now, I still don't understand. I can remember a vague feeling

that his work was 'really old' – much the same feeling I still have

towards Poe – and perhaps it was this sense of antiquity and

obsolescence that fueled the general lack of enthusiasm for his work

that pervaded in the geek/nerd circles I ran in back then.

I

did know one guy who loved Lovecraft, though... to the extent that I

could never get this guy to read any Colin Wilson, because, he said,

Wilson had pretty savagely ripped Lovecraft in some review, and this

my buddy could never forgive. It was this same buddy, Dick Pero, who

loaned me a much older hardcover anthology of Lovecraft's stories,

and it was within the pages of that lovingly worn collection that I

first discovered “The Color Out of Space”.

I

was impressed, on that first reading, by the palpable aura of

disquiet and unease that permeated the story... that creeping sense

of nervousness that increases by steady increments into dread and

then goes straight into full fledged terror, not because there are

monsters leaping out of basements and dragging screaming victims off

to be tortured and devoured, but because... things just... aren't...

right.

Still,

at the time, it didn't hook me. When I gave the book back to Dick he

was clearly disappointed when I told him, yeah, I'd read “The Color

Out of Space” (which he'd told me was a great introduction to

Lovecraft) but I hadn't liked it enough to want to read anything

else. The antiquated phrasing hadn't done anything for me, and

Lovecraft's writing style seemed to me, at that time, to be

cumbersome and lumbering, as compared to the simple, point to point

prose I was more accustomed to in the writers I liked – Heinlein,

King, MacDonald, Laumer. Plus, at that time in my life, I was looking

for something more upbeat, something where, yeah, you could drag your

hero through hell if the story required it, but goddamit, I wanted a

happy ending. And “The Color Out of Space” certainly doesn't

have a happy ending, and in point of fact, although I didn't know it

then, there are no happy endings in the Lovecraft Mythos. (Well –

Nathaniel

Wingate Peaslee kind of has a happy ending in “The Shadow Out of

Time” – he gets put back in his body after being mind-napped by

the Great Race, and later proves to himself that the experience

really happened, which sends his reason tottering to the very edge of

the abyss of madness. That's about as close to a 'happy ending' as

anyone gets in a Lovecraft tale.)

At

the time, I was not sophisticated or mature enough to understand that

some stories don't provide us with a pleasant escapist experience

because the setting is so much cooler than the real world, or the

characters are so much more interesting and fun, or the resolution of

the story is so upbeat and cheerful – what we would call today a

'feel good ending'. Some stories provide a different service –

they take us to an imaginary world and show us people and events that

make us appreciate the real world we all live in by comparison.

Lovecraft's

universe is very much one of those that makes you shudder in relief

when you re-emerge from it into mundane reality.

When

I eventually did start reading a lot of horror, I found most authors

were anything but subtle. They'd come at me with gore and violence

and psychos and monsters shambling in and out of the shadows, shaking

severed heads and bloody scythes at me.

When

I once more picked up a volume of Lovecraft, on the other hand, in my

mid 40s, I found his approach to be entirely different. Lovecraft

preferred to tease and torment me with descriptions of things that

seemed completely, prosaically mundane, utterly normal, screamingly

typical... except that, somewhere, somehow, he always managed to

imply that there was something terribly, terribly wrong going on...

something awful and horrible and unthinkable and unimaginable, behind

the paneling, or at the bottom of the stairs, or down the hallway

behind that nearly closed door.

Lovecraft

certainly had his limitations as a writer. His characterization is,

to be kind, rudimentary and basic (to be cruelly truthful, it is

generally just kinda shitty). And his plotting isn't much... in his

better stories, there is little plot at all, just a really incredibly

atmospheric description of a horrifyingly creepy situation where

nothing much happens, but still, you're completely freaking out about

it anyway. In his longer stories, where he has to give us some kind

of plot, I usually got the impression he really had little idea what

he was doing - this is especially true of “At The Mountains of

Madness”. Although one of these novellas, “The Case of Charles

Dexter Ward”, is, to my mind, probably Lovecraft's masterpiece in

spite of all his failings and problems with his craft.

As

I've said, I didn't give Lovecraft another serious try until I was in

my mid-40s. I'd been out walking in the Highlands section of

Louisville and come across a small, local bookstore called

Carmichael's. Inside, on the remaindered table, was a huge black

volume bound in cheap fake leather that said COMMEMORATIVE EDITION –

NECRONOMICON – THE BEST WEIRD TALES OF H.P. LOVECRAFT. It was

marked down to $9.95, and, hey, I'd been a sci fi/fantasy reader and

writer for thirty years or so at that point so of course I'd heard a

lot about Lovecraft – maybe, I figured, it was time to give him

another shot.

The

first story in that volume is “Dagon”. I started reading it, and

I was lost to the world around me.

Lovecraft

is a great writer, a brilliant writer, a historical and important and

seminal and frankly epic writer... but for all that, all Lovecraft

really has going for him, beyond his brilliance as a world builder,

is his ability to create mood, to evoke setting, to enact atmosphere.

But he's such an utter master at this, he's so incredibly,

astoundingly good at it, he is, in fact, so utterly without peer at

accomplishing this not insignificant literary task, that it doesn't

matter that his characters are two dimensional at best and his plots

are often sadly muddled and meandering things. In fact, if he were

better at characterization it might get in the way; the very flatness

of affect of Lovecraft's hapless heroes often makes it easier for the

reader to identify with them.

Lovecraft

is generally credited as being the first writer to create a

consistent imaginary backdrop in which his poor heroes not only never

win, but honestly simply never could. Lovecraft's universe is a

cruelly indifferent one, populated with hideously alien and ancient

entities of incomprehensible power who care no more for humans than

humans care for the dust beneath our feet.

In

a Lovecraft story, you 'win' if you manage to die quickly, and in

your right mind.

Very

few people in a Lovecraft story 'win'.

For

all his limitations, what Lovecraft did well, he was unsurpassed

at... and still remains so, nearly a century later.

In

my previous anthology, The

Zombie Ray From Outer Space And Other Pulp Tales,

I've discussed at length my love of 'pulp fiction'. Lovecraft was

certainly a pulp writer; he wrote of larger than life events and his

talent lay in evoking a visceral emotional response in his reader.

As I mentioned there, I love reading pulp and I love writing it, and,

in fact, several of the stories that I included in TZRFOSAOPT were

overtly inspired by Lovecraft, and because they're already in that

volume, they do not appear here. If you want to read “The

Eldritch Horror From Beyond The Nether Void", "The

Captain and the Queen", "In The Service Of The Queen",

or "Clowns",

you'll have to look them up there. And you'll find a lot of other

cool stuff there, too, and I hope you like it.

But

there's a great deal of stuff in this anthology that didn't make it

into ZOMBIE RAY, stuff that, while it's certainly in the Lovecraftian

tradition, isn't written in a particularly pulpy style. (And, on the

other hand, there's at least one story – “The Webbing Between The

Worlds” – that definitely is. But I hadn't written “Webbing”

at the time I put together ZOMBIE RAY.)

I

love to try to follow the roads that Lovecraft has surveyed and laid

out, if not quite fully paved, for me. There is a special pleasure

for me in trying to follow in Lovecraft's literary tradition, because

the challenge there is to construct that sense of tangible dismay and

unease that, increment by increment, one delicate shade of slowly

increasing fear after another, builds into dread, and then alarm, and

then, utter helpless horror... and to do it with some subtlety,

through a sense of deepening, thickening atmosphere and steadily more

ominous and creepy nuance.

I

don't do it as well as Lovecraft. I don't even come close. But I

enjoy the hell out of trying. And hey, nobody else does it as well

as Lovecraft, either, although a lot of us keep on keepin' on.

Lovecraft

has, of late, become tediously controversial to some who choose to

dwell on the things that made him an ordinary man of his ordinarily

unpleasant time (although, really, all times are unpleasant when

examined by outsiders; it's the human condition). Yes, it's hard for

a person of modern and enlightened sensibilities to read “Herbert

West, Re-Animator” and not feel repelled and sickened by the

obvious, awful racism redolent in some of its passages. That

Lovecraft was reflexively, unthinkingly a believer in the

reprehensible things his reprehensible culture took for granted –

awful things like the supremacy of whites over non-whites, and males

over female - can't really be debated. But we don't revere our

geniuses for the things that made them like everyone else. We

respect them for the things that set them apart from their peers, and

that still set them apart from us. Lovecraft the man was much like

his writing – for all his flaws, he towered above his

contemporaries, and he still casts a long shadow over the horror

fantasy realm he helped to invent.

I've

enjoyed reading every Lovecraft story I've encountered, and I've

enjoyed writing every story in this collection, and I'm sharing them

with you in the hope that you will enjoy them as well.

In

the end, that's really all the justification any writer needs, isn't

it?

D.A.

Madigan, December, 2019

INTRODUCTION

– THE WEBBING BETWEEN THE WORLDS

My

opening story in this antho is a pretty straightforward Lovecraft

pastiche. It does take some liberties with some established Mythos

canon – or, as I like to think, it fleshes the “Starry Wisdom”

out just a little bit more.

But

in writing this I did my best to ape Lovecraft's own writing style as

closely as possible – so much that between the archaic textual

technique and the length of the tale I find it doubtful I'll ever be

able to place this story anywhere but here.

Still,

I enjoyed writing it and as always, I hope you, whoever you may be,

will enjoy reading it.

I

do think I addressed one failing the Lovecraft Mythos has always had

– a pronounced dearth of one of my favorite kinds of monster.

You'll see what I mean as you read.

THE

WEBBING

BETWEEN

THE

WORLDS

I.

Before

Attercop House stood on it, the land was still thought to be

accursed. Before the Attercop clan, with all their peculiarities and

oddities and strangenesses bought the acreage, it already possessed a

dark reputation as a place of peril, wherein one ventured only at

hazard to one's life and limb.

The

origins of this particular parcel of land's ominous aura are nebulous

at best. Yet even before a half acre of dense woodland in that eerie,

tree entangled vale was cleared for the construction of the House,

the site was already primordially dim and gloomy, drenched in shadow

and darkness even at high noon on the clearest day, heavily overgrown

with ancient, malevolent seeming timber that huddled almost sullenly,

fiercely guarding its root-embedded earth from the invasive rays of

the sun. The heavy drifts of elderly mulch, mold, and murky moss

that shrouded the ground beneath the shielding trees hid brambles,

deadfalls, and quickbogs beyond number. There was no telling how

many hunters, berry gatherers, explorers, or merely curious hikers

had gone down to their screaming or silent dooms in those tenebrous

tangles.

Comments

Post a Comment